New Orleans & Plaquemines Parish

New Orleans, also called the Big Easy, is considered one of the most distinctive cities in the United States, with its colorful French colonial architecture, its musical heritage and festivals, its creole food and historical mix of African-American, Native American and European cultures. However, this southern city of color and revelry is also a place where income and opportunities are divided along racial lines, part of the legacy of segregation. Poverty and violence are concentrated in poor black neighborhoods, such as the Ninth Ward, which were also the hardest-hit during Hurricane Katrina, the costliest disaster in US history. As the city struggled to rebuild and get back on its feet, the recession and the BP oil spill in 2010 took an economic and environmental toll on the recovery process.

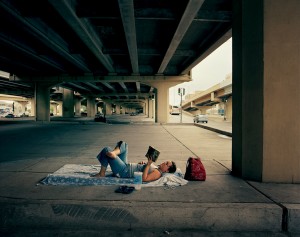

The people of New Orleans have faced many challenges and made much-needed improvements since the storm and oil spill, building new charter schools, improving access to low-income health care and reforming the criminal justice system. Much of the city has bounced back, but old black neighborhoods still have many vacant lots and homes. The local economy is still feeling the effect of lost jobs and the need for affordable housing remains high on the list of priorities.

PLAQUEMINES PARISH, LOUISIANA

For generations, fishing and farming have been a way of life for the rural communities of Plaquemines Parish, a thin stretch that follows the Mississippi River and juts into the Gulf of Mexico. Surrounded by water, the region, which is located 12 miles south of New Orleans, is particularly storm-prone and the residents that have settled here have developed a reputation for resilience and recovery. But a series of recent disasters have left the community reeling and wondering if it’s worth trying to rebuild their lives once again.

In 2005, the parish suffered catastrophic damage in Hurricane Katrina, with a storm surge of more than 20 feet, and the subsequent failure of the levees. The area’s seafood industry, which exports millions of pounds of shrimp, crab, oysters and fish annually, took a major hit, losing about half of its shrimping and shellfish industry, and more than 2,400 poor residents were displaced. The BP oil spill of 2010, the largest accidental oil spill in history, killed 11 people and leaked roughly 200 million gallons of oil into the gulf. According to The Center for Biological Diversity, the spill killed or harmed approximately 82,000 birds as well as more than 6,000 sea turtles and 25,000 marine mammals such as dolphins. BP says they have spent $14 billion on clean-up, but residents remain unconvinced about safety and worry about long-term effects. More recently, Hurricane Isaac wreaked havoc in the parish, washing up tar balls from the oil spill again on the shores of Louisiana’s Gulf Coast.

Many of the locals say the government has not passed effective legislation to make drilling safer and prevent another oil spill. They have lost faith in the government’s ability to stand up to big corporations like BP, at the expense of public health, wildlife, the environment and the local economy. “It’s not the power of the people anymore. It’s the power of the corporations,” says Kindra Arnesen, the wife of a shrimp fisherman that was affected by the spill. They fear their traditions and livelihood are being destroyed by economic interests and environmental degradation, as the wetlands disappear and the land sinks further below sea level every year.